An overview of the Maltese antique furniture market will clearly indicate that the recent past has seen an ever growing awareness for that which surrounds us, in contrast with an earlier general disregard for furniture of Maltese manufacture when compared to other existent and imported furniture. In no way can such a generalisation be taken seriously, unless a clear perspective of the times, buyers and attitudes is considered.

The trends that have changed and evolved over the years would be unnecessarily difficult and confusing unless one were to bracket the decades involved: The 60’s & Independence, the presence of the British Forces. The 70’s and early 80’s, The Mintoff years, Banking Policies, Republic Malta; The Late 80’s & 90’s, Property price boom, thriving business & tourism.

DECADES. The trend of the sixties and seventies was of considering foreign furniture the more prestigious, while Maltese pieces were hardy recognised as local in manufacture and given little importance. Thoughtfully, it is not a question of comparison. Maltese furniture on the local market has been around, as auction catalogues witness.

Being Maltese did not carry much weight, as appreciation for local crafts was poor; nor did it carry much prestige, as goods coming from older and bygone eras had very little placement in new collections. Notice the absence of a museum dedicated to Fine Arts – the pieces of good furniture adorning our museums are secondary and only compliment the vast collections of bequests on the walls.

In catalogues from the 1940’s ‘EM’ standing for ‘English Made’ frequently embellishes descriptions in catalogues, while descriptions distinctly do not indicate anything Maltese; except for the famous ‘Antique Maltese wall clock’. Today we commonly find ‘a Maltese painted deal stool. The eighties saw a change to appreciation of the local goods while in the late 80’s a strong purchasing power dictated the market and gave it an upward trend. One of the main reasons for the said flowering of Maltese furniture can be considered to be a new generation of buyers. The generations that followed the war, and those that had a fairer chance at making a good living reached the market scene; The rationale of most of those who went through the war and had seen a stable antiques market with little import and plenty of supply had had an early field day. 1989 also saw the important and unprecedented book of Antique Maltese Furniture by Joe Galea Naudi.

With reference book in hand, the nineties show a strong recognition for all Maltese and an increase in prices unequalled in the earlier years.

Style and quality are not under review. The availability of a healthy mix of Maltese origin furniture from the 17th to the 19th centuries with the imported furniture available in shops and auctions must be analysed upon its own merits of individual choice and values. Today the choice is still readily available with some distinct differences. Maltese furniture takes pride of place in all establishments. The values and their steady increasing prices are a clear pointer towards where the market is going. Maltese furniture, like Maltese arable land is in short supply. No excellently executed reproduction furniture will replace the real thing. Foreign furniture, for it is essential to realise that importers have broadly opened their markets on the continent, now commands high prices in the prospective countries. Good quality goods are expensive and have increased in value at a rate higher than that of more middle-of-the-road examples, when compared to several years ago; Container space comes at high premium, as does travel and time. Dealers necessarily need to buy their stock briskly. Their favourite haunts do not always deliver on the required days. The space is filled with what they think can sell at a fair profit. I have often seen foreign invoices and bills with values that I realise would have put most dealers on the spot to hurriedly ship their goods. Once on our shores, the better pieces find their way to good homes in no time. The remaining stock slowly find its way too. In shops or at auction the buyer has a field day.

ENGLISH IMPORTS: In the 60’s and 70’s, from an auctioneer’s point of view, the upper crust of relevant goods at auctions dealt mostly with imports from the United Kingdom, these in themselves, mostly furniture from the mid-19th century, of good quality and available to dealers in quantity, together with some fine continental pieces found in England. Mixed in were the rich, ornate secretaires embellished with pietra dura, painted glass panels; English walnut from the Victorian and Edwardian periods, good Regency mahogany dining room furniture, all packed the crates together with an extensive array of boulle, (ill no 1) ebonised and marquetry furniture in the French and Continental manners. It is very relevant that Maltese dealer-importers regularly discuss and reminess their ability of purchasing good stock from the UK; of English dealers who eagerly await the locals in the hope of selling pieces they had no market for during the time. Ebonised furniture richly inlaid with ivory mostly from the mid 19th Century, was un-saleable in England in the 1960’s, and thus available at a fair prices (dealers say they were begged to make offers for these pieces). Grand-father clocks, walnut cabinets with brass mounts, all furniture types that filled the container loads brought over. Most furniture considered foreign by the English dealers was more accessible and commanded a relatively lower value than the English better quality examples. Generalising to discuss the quality of these pieces is unfair. Most were well made genuine examples of English furniture. (ill no 2).

Above: Images cutesy of Ivan Vassallo of Vassallo Antiques, valletta

Maltese dealers purchased certain stock with specific customers in mind. The buying community was well known and not very numerous. The Upper echelons of the British services were conspicuous at dealers and auctions, and formed a formidable part of the scene. Their departure from our islands also allowed, not only for the dispersal of good English furniture that they had brought out to Malta, but, for the export of quality Maltese pieces that today find their way back to our shores via auctions in London. It is this furniture in abundance, and presented as the thing to own, that plays an important role with respect to changing appreciation and trends of decorating our abodes. It is without doubt very significant that dealers set a trend by presenting the local community with pieces, although of good, some very good, quality, that were not selling in their country of origin. The mirror effect, the export of Malta made goods, is also of some significance. While furniture brought from the Continent were less appreciated at source, the shipping of a broad category of goods bought by local dealers and sold to Italian counter-parts showed a marked difference, in that, at auction, dealers paid slightly more than the average local auction-goer, always knowing that a ready export market with benchmarked prices was awaiting. Maltese 18th & 19th century olive-wood serpentine large chests (ill no 3), angular dining room large showcases and bookcases were noticeably more popular in Sicily where higher prices were being achieved. The marked difference is that the local market prices were being determined by those of neighbouring countries. The local buyers could not catch up with rising prices, and goods earmarked for export were shipped relentlessly. For many years, typical export goods were bought repeatedly by the Maltese trade, often working hand-in-hand, grouping goods and securing prices and profits. The proportion of the local antiques market compared with the volume being exported is of great consequence. Evidently, the export of Maltese wares has had a blunt effect: the diminishing quantity has now made these pieces more sought after. The lack of angular showcases on the market in the mid-to-late nineties certainly was influenced by their earlier export, and their unavailability has seen price hikes significantly larger that other furniture of the same type, for example, Malta made sideboards which are still very common. The Maltese market hiccuped to an artificial export-determined level. Until export of all Malta made goods was stopped categorically, the market for these goods remained buoyant and only saw a slight dip when export ceased and the local scene kicked in. The timing worked out well as it also coincided with a more appreciative late 1980’s.

Typically, no statistics or selective records are available to show the volume and quantity of imported furniture classified as ‘antiques’. Paul Vassallo is known to have started his importing business around 1948, bringing 2 or 3 crates annually, while his brother followed suite in 1962 importing the same volume. The brothers had the lion’s share of the market until the mid – 1960’s when other dealers took up the same line: Ralph Arrigo, Paul Borg, Paul Tanti. The best recollections of importers indicate an approximate 2 x 20ft crates annually. Export on the other hand, covers also foreigners who returned to their country of origin. It is clear though that the ratio of container imports-to-exports stands at 30:1. The auctioneer approached to conduct an auction in a house always looked for the added bonus of including goods that were appealing and saleable, often selecting from dealer stocks those pieces conveniently fitting into the houses. One must consider that the few auctioneers in Malta had a voluminous locally sourced supply. Mixed in with the unappreciated Maltese olive-wood furniture appeared local ‘victoriana’ – the Maltese version of the early Victorian style excluding all the revivals of the mid 19th century. To all local auction goers, the mix was created conveniently, and over the years became customary, as up to this very day, most collection accumulated over the past 3 decades are a fair conglomeration of foreign and local styles.

With the arrival of truck-loads of goods for auction often accompanied by a phone call to inform of their arrival, previously unseen goods turned up at the auctioneer’s door step awaiting new owners. The choice was plentiful; the prices agreeable, the owners glad to be rid of their ‘secondary’ surplus. The connoisseurs with a keen eye picked up whatever took their fancy for a moderate fair price. Cartels and groupings were left for the auctions of goods from the Army Surplus and British Forces auctions.

THE 70’S. A hand written note book from a prominent local dealer shows the prices of imports: Georgian sideboard Lm 35; Victorian sideboard Lm 22; Ivory inlaid ebonised table 45; 7 Grandfather clocks Lm 440; Boulle card table Lm 310 and credenza Lm 155; Georgian work table Lm 40; Edwardian 7-piece inlaid suite at Lm 135; Oak Welsh dresser Lm 38; Regency card table Lm 80; Catalogues from the first auction at the new Belgravia Auction Gallery run by Moses Sammut show illustrations of mostly foreign furniture of good quality.(ill no 4). Auctioneers worked closely with their preferred dealers, who healthily sold and bought at auction generating much business and, as always, guaranteeing that the private sellers got a more than fair value for their belongings. The turnout is much healthier at good auctions today. The pitfalls of this relationship between auctioneers and dealers were unseen. Word of allegiance between auctioneer and dealer did no good for the local market in the long term. It created a false sense of supply of goods. The balance of supply and demand was catered for. The shortage of Maltese goods felt today could never be felt earlier as the lack of supply was buttressed by imports disguised as local sourced goods in houses and galleries alike. Such was the trend. When the supply of Italian / French replicas of the late 70 and early 80’s hit the local scene with a vengeance, the alarm bells were ringing. Honest cataloguing ran a knife-edge as auctioneers, knowingly or not, were taken in by these magnificent creations. In this arena it was high time to severe the link. My father, a man of a thousand local sources, slowly shifted the sale room to take all that came from his faithful private vendors. That was easy. The local scene was plentiful.

THE 80’S. Since the 80’s we have moved to a less overwhelming foreign furniture supply, to a more mundane but often surprising Maltese furniture, generating the bulk of our turnover. Up to the recent past, the supply was plentiful and the buyers ready with their money. It is to be noted that stringent restrictions on the importation of antique furniture, indeed all furniture, under the auspices of protecting the local manufacture saw a closing of the foreign market completely, except for pianos and similar goods that were brought in as instruments, thus avoiding the restrictions. Subjectively, this could have triggered the local scene to a more inward looking search for goods that has become a strong wave for the appreciation of Malta made furniture in general. Today the scene is very different. Demand for high reserves on presented goods is our daily struggle; To convince vendors that an exception is not a rule, and, that quality and condition should be strongly considered, makes or breaks a sale. The patronage of our gallery has changed very little. The Maltese lawyers, doctors and their like have regularly frequented our sale-rooms, rubbing shoulders with budding industrialists and the business community. The earlier absence of the younger generation, the new home maker, the upcoming business man, of the past 30 years has been reversed in the past years where confidence in the market and fair values has brought out the best in cunning and foresight. Running parallel with this is the mushrooming of dozens of dealers, all with a good source and a niche market to cater for. This increase in antique shops, younger generation buyers and high prices, runs along the same years of a stronger awareness and knowledge for the antiques world. Fairs, exhibitions, antiques courses, well advertised and attended auctions all contributed to a general strong market feeling. The business community has also made a significant presence, although their purchasing power is often reflected by economic activity in Malta; The property boosts of the nineties ran parallel with a serious increase in the price paid for local important pieces.

PRICES . The older generation has shown a willingness to express themselves on the prices that they used to pay for their fancies. Those who still own their purchases are more eager to say that the pieces were bought for next to nothing, while those who sold would readily vouch for massive profits. Bureaux (ill no 4) were few and far between, being undoubtedly the most prestigious piece of Maltese furniture available.

Chest of drawers are more common. The large serpentine type in olive-wood and often mixed with mahogany moved determinately upwards; The price in 1974 was around Lm150. By the late 70’s average prices of Lm300 were being paid. In the mid 1980 the price was Lm 1000 while Lm3000 was reached by the early 1990. Oval Maltese 19th century mahogany tables of medium size ran parallel but at a lower level: 1975 Lm 80, 1985 Lm 300, 1990 Lm 600, in 2000 Lm 1000. The general trend of price increase follows this pattern very closely in that Maltese well made 19th century olive-wood furniture increased in price significantly more than their dining room pieces in mahogany; sitting room furniture was more acceptable and desired.

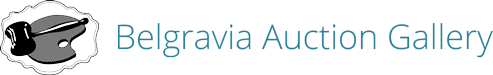

In 1995, I was asked to conduct an auction in Attard by the daughter of the Late Prof N. Curmi. The auction was held in-situ, where the collection had been left for many years. In fact the collection contained, in the broadest sense of the word, something for everyone. I was fortunate to be given some auction catalogues from the times when Prof Curmi was attending auctions and buying in the 1940s. Some receipts showed the prices paid, and as many of the lots were included in the 1995 auction, a comparison of prices then and now follows (See table: right). I have picked the items which were definitely identified, some of which can be seen in the illustrations of the house just before viewing. (ill no 5) (ill no 6) I have also thought to remark on some interesting lots that were bought in the middle 20th century auctions, with which I will start.

Above: Images from the Curmi auction

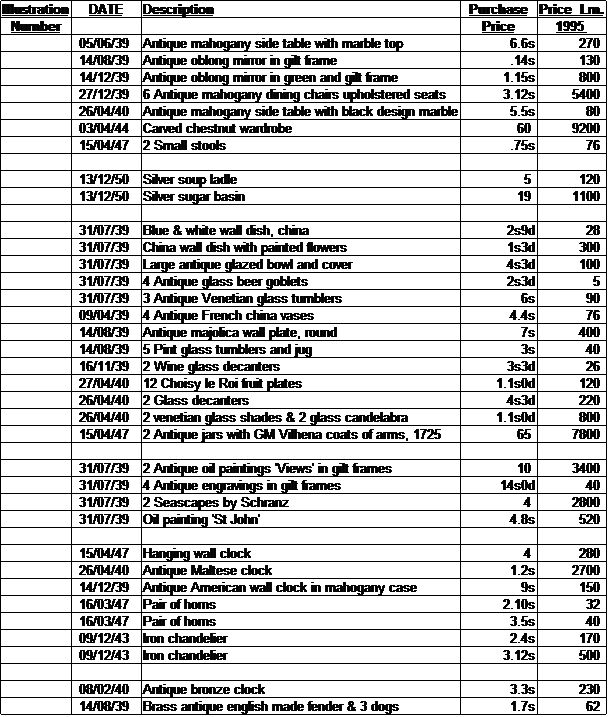

4th December 1950 saw an 8th day auction of the contents at 12 St Paul’s Square, Notabile belonging to the Late Rev. Mgr Gius Vassallo, (ill no 7) described in the catalogue brief as rich, artistic & genuine household effects… . These included lot 896, An extremely rare Sedan Chair, richly painted with figures, complete with fine bronze mountings and internal silk hangings. The Coat of Arms of GM Cottoner are painted in full colours at the back.

Lot 1077 A fine veneered all sides inlaid 17th century chest of drawers with coat of arms of DeVilhena and that of Portugal.

The catalogue reads like a museum inventory. The paintings include David Teniers, Jean Pillement, Jan Brueghel and many local artists. The word Malta or Maltese to describe any piece of furniture is completely absent from the catalogue.

The year 1949 saw an auction of ‘The Exceptional Fine Collection of Antique Paintings, about 130 pieces in all, by well known Masters, property of the late Prof Antonio Sciortino at 59 Granary Street, Floriana.

This is the rich cultural heritage that went, and indeed goes through auction rooms and is accounted for. The same cannot be said for goods which change hands privately, for which no record can be kept for posterity.

The following table is a comparative ‘bought and sold list’ of items, which, from catalogue descriptions and receipts, allowed a positive identification of lots present in the 1995 auction. The data shows a meteoric increase in prices, which if projected, will see our sale – rooms bursting at the seams with investors!

A significant remark is that expensive items in the mid century are again the higher prices in the 1995 auction. Brass, china and objects of low value, although showing a hefty price increase, are not relatively expensive today. Also pertinent, the pieces purchased then as antiques have added another 60 years to their tally.

The auctioneers catalogues come from most auctioneers selling at the time: Frank A Cohen; Joseph Darmenia; Alb. C. Gingell; E Gingell Littlejohn (Jr); GN Santucci; SE Falzon Santucci. In May 1939, FA Cohen sold lot 898, an alabaster statue of St John, under glass case, bought for L2.8s and sold in 1995 for lm800. (ill no 7) Lot 517..Antique mahogany sofa upholstered in brown damask, bought for -17s (ill no 8). A very good solid mahogany dining table to seat 12 for Lm2.12s; English made rocking chair for 10s; Antique Louis XV armchair with red plush, in black & gilt fro Lm1.2s; Pianoforte by Kriegelstein for 4s9d; 10 antique views of Malta in frames for 2. 18s; 2 Antique mahogany corner tables with black marble for 3.6s; English made mahogany dinner waggon for 2.4s;

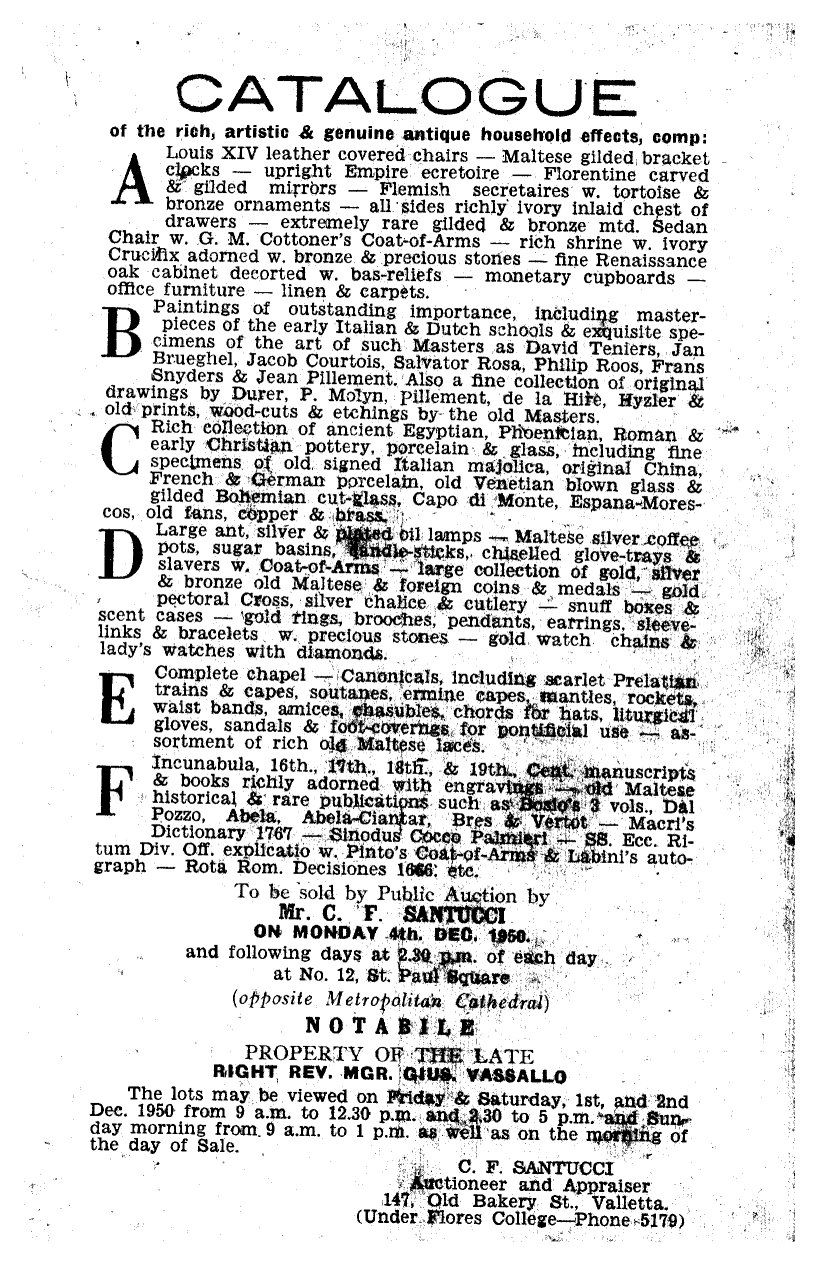

Above: Belgravia Auction Gallery auction setup mid 1980

The Maltese antiques business has its own grapevine. The salient prices achieved, whether at auction or privately, are news in no time. Benchmark auctions, auctions where attendance and prices are above average tend to create a stir. Not only, but the distinctive values of certain items at auction can occasionally be benchmarked. The auction of the late Dr Joe Borg in Tigne Sliema in early 1997 saw an unprecedented increase in prices of good quality engravings. M Bellanti lithographs previously selling at auction at around Lm 250, reached Lm500+ and were repeated in other auctions that followed, like the Briffa Brincati Valletta auction. The trend was sustained for a while. The same can be said for Schranz / Testa views that went beyond the Lm1000 mark. The Tigne auction also saw an unusual phenomenon: An individual purchasing in a short time several Maltese pieces of 18th & 19th century furniture. As the individual attempted to buy repeatedly the prices achieved and the short supply created a stir that saw 19th C. Maltese serpentine chests selling at Lm6500. Four years later, the lull that followed is still with us, and recently the prices are again more relative to other goods. Dealers Mrs Doris Mizzi, Mr J Vassallo, Mr Ivan Vassallo and Mr Alfred Tanti discussed the import of furniture in the 60’s and 70’s at length. The majority of imports were brought form the UK and consisted mainly of furniture. All agreed that UK dealers would reduce prices drastically to close a deal; making an offer brought you very close to a closing a deal.

Perspective. While readily conversing and having a healthy relationship with most dealers and the public, all readily agreeable to a chat about local market trends in Malta, The auctioneer has a tight-rope balancing act of a job, in that he is often asked to evaluate and sell by the same person. He also must advise prospective purchasers without pushing his loaded opinion. He is invited and shown collections, private hordes and singular items where his confidentiality and secrecy is paramount. Having lived this throughout my adult working life I must admit that the conclusions drawn above are also surprising to me, and that when searching for reasons and justifications of the temperamental local auction and antique market I was unaware of the close knit and fragile conditions that we work in. We handle history and must do so with delicate hands.